# 20 I’m Stoned, But I’m Not From the Stone Age

On tolerance, right-wing politics, and overtourism—Amsterdam, the Netherlands

I walk through Amsterdam’s city center feeling hungry and hot. Unpredictable downpours have made it hard to enjoy the streets, so now, on this warm cloudless day, I’m keen to roam and get lost.

I’m less keen, however, to do so with hundreds of disoriented tourists high off their heads. The use of marijuana on the street is supposedly banned, yet I walk in a cloud of sweet (and not totally unpleasant) smoke.

August in Amsterdam—what was I thinking?

According to the NYT, Amsterdam drew a record 23 million visitors last year and is one of the most heavily touristed cities in the world.

Bicycles clatter by on the cobblestones. Canal houses lean shoulder to shoulder to avoid imminent collapse. On front doorsteps, signs speak up for their residents: “Please respect our privacy and don’t sit here.”

I cross one bridge after the other to get away from the crowds or seek the shade of trees. It’s past lunchtime and I need fuel. The terraces are either full or unappealing, offering overpriced hamburgers and fried foods. For someone intolerant to gluten like me, a sandwich on the go isn’t an option and it looks like I’ll have to content myself with supermarket snacks, baby carrots with hummus or unsalted mixed nuts.

Vaguely curious, I peek into the red-light district, then quickly change my mind.

On Rembrandtplein, packs of intoxicated first-year students cross my path. I think of my own years at university. How much we drank and how heavy drinking gave us social standing. The wisdom of initiation rituals escapes me now. It seems harmful to promote drunkenness as a way to fit in.

Tolerance

Amsterdam is known as a city of tolerance. You have the right to practice your religion here and express your (sexual) identity. Many churches wave rainbow flags. As long as your behavior doesn’t negatively impact others or break any laws, you’re free to do as you please.

I’m proud of this reputation.

People here use common sense to judge what’s socially acceptable. Nothing is too crazy per se, and you’re not likely to be reprimanded for disrespectful behavior, yet when you obviously act like a selfish brute, bystanders might say: Doe normaal, zeg! (Act normal!). It’s a self-correcting system that works most of the time. We can live together without excessive legislation if we all agree to be socially mindful.

Tensions

Today, though, I walk around like a critical voyeur. I just spent three months in Japan, were the majority of people conduct themselves as modestly, unobtrusively, and unpretentiously as possible. My perspective on what’s socially acceptable behavior has changed and Amsterdam is a bit of a shock. People here regularly bump into me with their backpacks, block my path or cut me off. And should we really ingest as much drugs as possible just because it’s allowed?

I haven’t lived in the Netherlands since 2001, and once you’ve left your home country for a while, there’s no going back. Home will never be home again. A certain self-consciousness is now present, a distance, an evaluation. My 107-year-old grandmother understood this perfectly and kept asking me the same question: “Do you feel much has changed?”

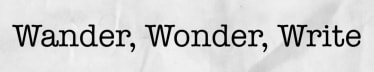

I gulp down water and focus on what pleases me. Citizens of Amsterdam are fascinating. They dress with flair and individuality, mixing headscarves with colorful dresses or sleek suits with platform sneakers. Many look like children from the flower power generation. Because of social media, even tourists seem to make a style effort these days; a selfie can be just around the corner.

In the span of a few minutes, I pass sex shops, flatbread bakeries, antique stores, halal butchers, vintage clothing shops, shoarma joints, coffee shops, and Italian ice cream parlors. I like what I see. Walking around in Amsterdam, watching people enjoy life, you get the idea that diverse humans living in harmony with one another is not such a farfetched idea after all.

But under the surface, tensions brew. There are 18 million people in the Netherlands, a country not even half the size of Ireland (with a population of 5 million), and problems arise when you start to disagree on what’s socially acceptable behavior.

Political Climate

The Netherlands held their general elections last fall, and almost a quarter of voters chose the right-wing party of Geert Wilders, known for his anti-immigrant opinions. I felt disappointed and ashamed.

In the past weeks, I’ve spoken to family members, friends, bus drivers, salespeople, and random strangers across the political spectrum to get a sense of my country’s mood. Some left-leaning people are close to despair; others believe the right-wing coalition won’t last. With little governing experience and few achievable plans, Wilders and cohorts are bound to fail.

I was particularly curious about people who usually vote on the left side of the political spectrum yet switched sides. What had made them change their mind?

Some said: “We have an affordable housing problem. We need to fix this problem before we can let new people in.”

Refugees are obviously not to blame for this, and an immigration stop won’t solve the problem, yet I understand why some Dutch people are upset.

Another opinion was: “Our tolerance has stretched too far. It’s backfiring. We need to protect ourselves from ideas and practices that are harmful to our society.”

This didn’t concern drug use. This was about how the previous government supposedly has done little to stop the spread of fundamentalist Islam in our country. How they’ve allowed conservative imams to preach against gay and women’s rights and incite hatred. How they haven’t differentiated enough between peaceful gatherings advocating an independent Palestine and extremist Muslims threatening Jews with violence.

I did not vote for Wilders and am not tempted by rightwing politics that promote xenophobia. But I, too, have zero tolerance for anyone threatening my fellow citizens or our liberal Dutch values. In a world bent on simplification and polarization, my words might be twisted, but I recently vowed to be less fearful, so here it is: We must limit the spread of harmful ideas—whether it’s fascism, fundamentalist Islam, racism, or something else entirely. We must protect our freedom and democracy.

Tourist Market

In the city, my search for food leads me to the Albert Cuyp market in the Pijp neighborhood, east of Museumplein. It used to be a typical Amsterdam market with vendors speaking in local slang. Over time, the market welcomed immigrant vendors from places such as Turkey and Morocco, and Dutch people from former colonies such as Suriname. They enriched the daily offers with more diverse products and gave the market an even truer vibe. Amsterdam, after all, with its 180 nationalities, is one of the most multicultural cities in the world.

But the market does not feel true to me this time. Most stalls have turned into food-truck-type eateries catering to tourists. Vendors address me in English, advertising their tacos, middle-eastern sandwiches, onigiri, Korean fried chicken, fries, and more. I don’t see evidence of an angry backlash at tourists, yet I imagine that residents who aren’t directly benefiting from the tourist dollars aren’t pleased.

“Tourism shapes our world-by which I mean it alters our economies and cultures, as well as our physical environments-in profound and surprising ways,” writes Paige McClanahan in The New Tourist, a book I recommend.

Fair Deal

One man with a shaved head and tattoos on his bare arms screams out his concept: “I wok healthy stuff! I get my organic veggies from local farms! I sauté your choice of noodles with your choice of protein or make it completely your way!”

I doubt the source of his ingredients, yet even supermarket veggies sound okay to me by now.

“Can you make a dish without noodles,” I ask, “just a whole bunch of vegetables with protein?”

His entire face smiles as though I’m his first customer. “Absolutely—watch me!”

“Wait,” I say. “You take cards?”

Although, I’ve been in Europe for three weeks, I’ve not yet needed cash.

He laughs. “I’m stoned, but I’m not from the Stone Age!”

I regret my order. I enjoy smoking weed from time to time, but I’m not thrilled about a stoned chef cooking my food.

He throws generous portions of vegetables and tofu into the wok. Before I can stop him, he also squeezes in an enormous amount of teriyaki sauce. I pick up the industrial-sized bottle. The main ingredients are sugar, salt, and wheat. Fortunately, I can digest enough gluten for this not to be a huge problem, but my lunch will no longer be healthy.

“Don’t worry,” he says. “I make all my sauces from scratch. I just use these bottles to store them.”

Right.

When he deems the dish done, he tries to pour his creation from the wide wok into the narrow takeout cup without using a tool to guide the food. Half of it falls into the garbage instead of into my cup.

I don’t object. I feel like it’s my fault for having chosen my vendor badly. In foreign countries, I tend to be more careful when ordering street food. More than duped, I feel sorry for the chef. I imagine him beginning the day full of high hopes, yet by mid-afternoon, when not enough customers have come by, he smokes some weed to take off the sting and sets himself up for failure.

He hands me the half-filled cup. I wave my bank card. He does something on his phone, sighs, swears, and looks at me, frowning.

“Do you have cash? My phone’s not working.”

So he’s from the Stone Age after all.

“I’m sorry,” I say, “no cash.” Then I remember something. “I have a five euro bill. Traveled with me from here to Asia and back.” I stuffed it in my phone case as emergency cash, as the replacement of the twenty dollar bill that’s supposed to be there for unexpected expenses such as taxi rides.

“I’ll take it,” he says. “You can bring me the other three euros on another day, if you want, when you’re in the neighborhood.”

I accept his offer. I’ll pay him some for the meal he prepared, and he’ll serve me some of what he promised to deliver. It seems fair.

Future Collaborations

On my way home, I pass by the Dam, the oldest of the city’s iconic squares. It’s surrounded by grandeur and soiled by pigeons. I observe the tourists and locals, and think about the future of Amsterdam, the housing problems, the protests, the inequalities, the rising seas—Amsterdam is already about 2m (6.6ft) below sea level.

One could say, and I’m saying it, that Amsterdam is built on the need for collaboration. Fishermen and farmers on the two banks of the river Amstel joined hands in the 13th century to build a dam and protect themselves from the sea. The dam bridged their sides, facilitating future collaborations, and from this dam the city grew.

Time to Say Goodbye

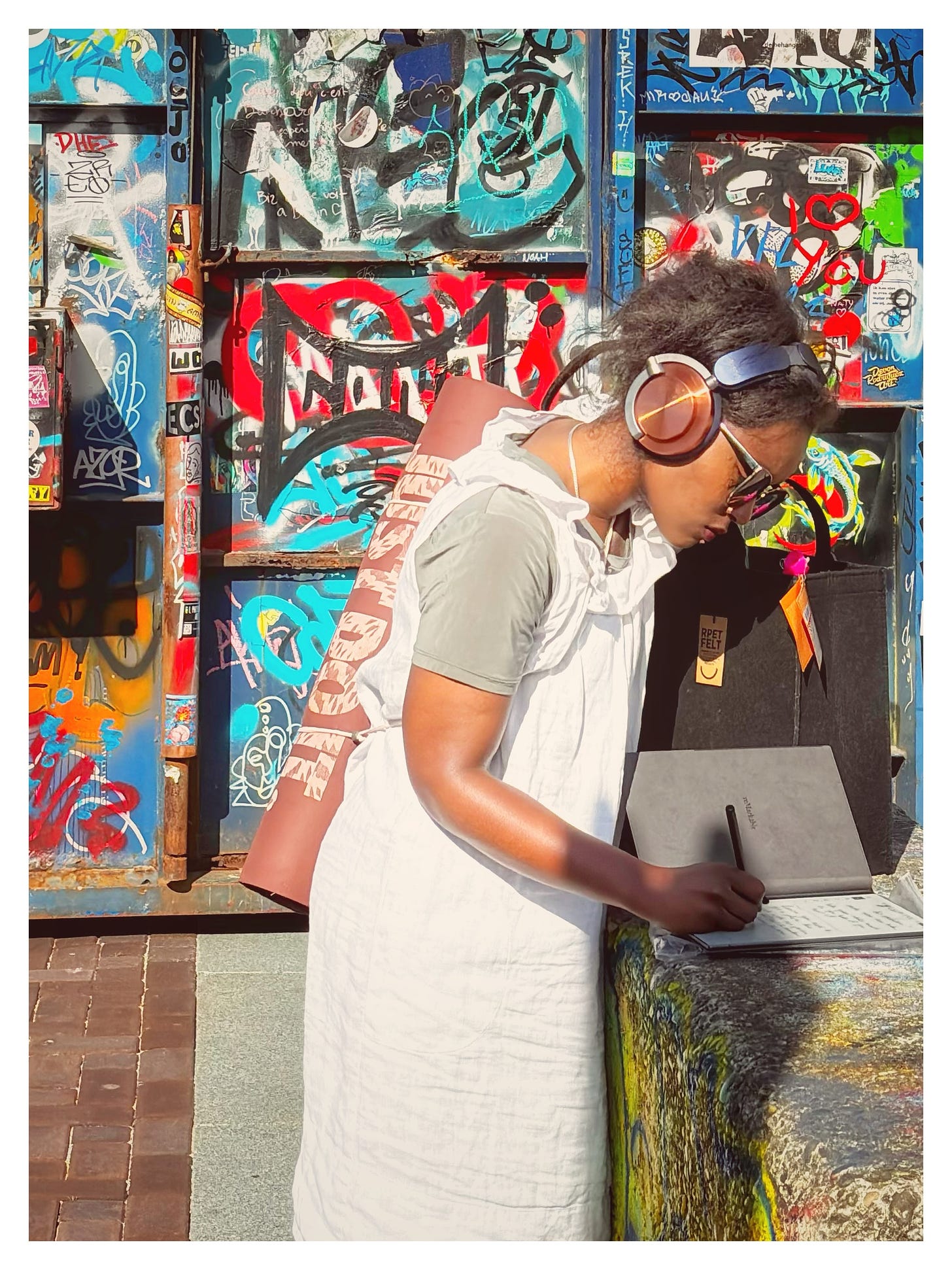

Thank you for traveling back with me to Amsterdam. All photos used in this essay are taken by Daniel.

Next week, I’ll report from Bracciano, Italy, where a mushroom festival is about to start—buon appetito!

All my best,

Claire

P.S. For those of you interested in yet unfamiliar with Dutch politics, I recommend reading this long article in The Guardian about pollution and immigration or the shorter election coverage in the NYT.

Fabulous essay, Claire--I especially love this line-"We must limit the spread of harmful ideas—whether it’s fascism, fundamentalist Islam, racism, or something else entirely. We must protect our freedom and democracy." Amen.

Some of my favorite memories took place in Amsterdam in the 90s and early 2000s. I used to have an office in The Hague--many, many moons ago. Rather than weed and sex shops, my interests involved the great jazz heritage --the extraordinary tenor sax player- Ben Webster lived in Amsterdam for 3 years in the 60s. I could (and did) spend hours perusing the vintage/antique shops. Thanks for taking me back....(I loved Amsterdam so fiercely, that a part of my novel takes place there.)

I was watching videos on gardening to learn about weed control. The most fascinating idea to me was that the problems with your soil determine the weeds you'll get because the weeds that flourish will be those that can survive and adapt to that soil. Just plucking weeds doesn't solve the problem. There are thousands of seeds always present in the soil, but only those that can take advantage of the soil conditions present will be the ones that grow. I also learned that the earth hates to be bare and will always find something to cover itself with. So stripping away everything that is on a section of earth is an invitation to weeds more than to whatever it is the gardener hopes to grow.

This is what I thought of when you said, "We must limit the spread of harmful ideas—whether it’s fascism, fundamentalist Islam, racism, or something else entirely. We must protect our freedom and democracy."

If there are problems in the metaphorical soil of a nation, trying to pull out each weed of a negative idea that sprouts won't work. You've got to be honest about the fact that something underlying it all is unhealthy. Let all ideas have their voice because when you have good soil and conditions, the good stuff you plant will grow. Controlling speech isn't the answer; rather, let MORE ideas get heard including ones we don't like. If they are terrible ideas, healthy soil will keep them from taking root. Plus we can start to understand where these terrible ideas came from and fix the conditions causing them to spring up.I think radical unnuanced ideas take hold when there's so much determination to crush every disliked opinion rather than acknowledge differences and nourish understanding of viewpoints so we can actually fix the problematic conditions.

In the end when people disagree, we can't all have what we want. Things swing back and forth just like nature is ever in flux, righting and rebalancing itself. I wish we could have perfection, but we can't.

Still, if you want the best outcome, you have to focus on creating the right conditions to achieve it, not simply stomping out each unpleasant weed. Democracy has no problem with bad ideas, the problem comes from trying to let only a few narrow ideas get through and squelching all unapproved discussion. Because you never get to the heart of what's really going on that way.