# 16 Naoshima, Japan: Can Art Make Right What Mining Wrecked?

On museums, hope, and transformation.

A cluster of islands in Japan’s Seto Inland Sea is nearly forgotten when the Benesse Art Museum opens its doors on Naoshima in 1992. Visitors from around the world travel to the region and more galleries pop up.

Contemporary art on abandoned islands? Daniel and I must have a look.

The Industrial North

We board a small ferry in Uno Port and take indoor seats because of the rain. High season is yet to begin and the boat is only three-quarters full. During the half-hour ride to Honmura, I watch the sea through the salt-smeared window. There rise the green hills of Naoshima, and there looms… what? Our first art project or a chemical plant?

Industrial vats occupy the bare-rock coast line. Chimneys cough up smoke as thick as wool. I quickly browse and find answers: Mitsubishi Materials has been operating a copper smelter and refinery on the island since 1918. The copper that drew my greedy ancestors to Nagasaki still puts its stamp on Japan.

I feel as though I’m witnessing something illicit. I’m not meant to see Mitsubishi, which might explain why there are only four small boats a day on this route. Most people travel to Naoshima on one of the larger car-carrying ferries that dock in Miyanoura. Instead of passing by the industrial North, these visitors are appropriately welcomed to the island by one of Yayoi Kusama’s iconic polka-dotted pumpkins, large and surreal like a Jeff Koons. Tourists are meant to see hope, not ongoing destruction.

Public-Interest Capitalism

The hope comes from Japanese tycoon Soichiro Fukutake, who long dreamt of reviving dwindling communities through art. When he met Chikatsugu Miyake, the mayor of Naoshima and priest of its main shinto shrine, the men thought up a plan. It was 1985 and Naoshima lay gutted and nearly abandoned after decades of industrial abuse. Could art draw new blood to the region?

The plan was more ambitious than “just” economic revival. Fukutake wanted to undo environmental damage. Make art a meeting place for locals and visitors. And offer urbanites a slow and contemplative alternative to hasty modern life.

His book, With Art As My Weapon: Revitalizing Rural Communities and Introducing Public Interest Capitalism (Long River Press, 2020), contains the chapters “Villages Are Treasures,” “The Economy Must Serve Culture,” and “Nature is the Best Teacher,” and makes clear where Fukutake stands. But after seeing Mitsubishi’s copper plant, I’m a bit of a sceptic. Is this a greenwashing campaign from a dubious corporation? Fukutake’s fortune does not come from the industries that wrecked the islands (he was a leader in education, language training, and senior care), and yet I worry that his plan is saying, Don’t look over there! Look here!

Honmura and the Art House Projects

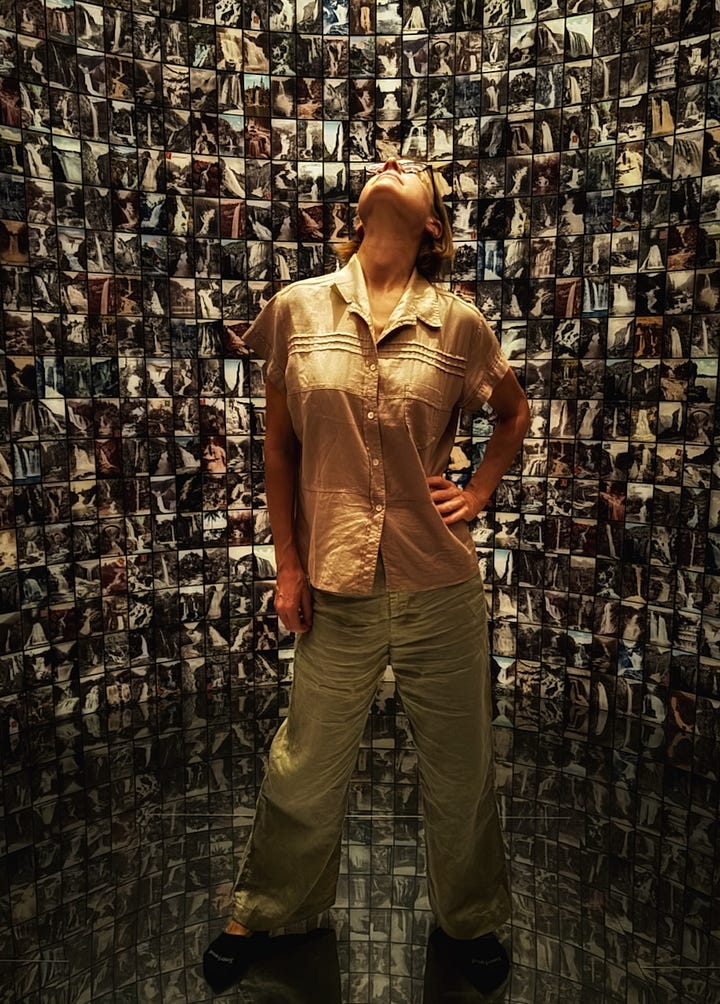

We get off the ferry, leave our luggage in a coin locker, and purchase tickets to visit the Art House Projects in Honmura, a fishing village you can comfortably walk through in an hour. Since 1998, artists have been giving abandoned houses a makeover. While keeping traditional exteriors intact, they’ve changed the interiors into galleries or even more imaginative spaces.

We receive a time-slot ticket for the Minamidera house, which allows about twenty people in at one time, and wait in line while receiving instructions: Turn off cellphones; be as silent as possible; follow directions from the interior staff. We’re led into a wooden building in the absolute dark and must keep our hand on the corridor walls to feel our way inside. We sit on benches and wait until James Turrell’s artwork starts to glow as if out of nowhere. Once our eyes are sufficiently adjusted to the gloom, we walk toward the light and marvel at what we can see, a living screen, a pulsing dream, a field without a horizon. Back outside, I’m strangely calm like after a long meditation.

We visit five other art house projects, some truly gorgeous, others less so, yet none as impressive an experience as the first. When dusk falls, Daniel and I hop on a bus and check into our tatami-mat room on a campsite near the shore.

It’s peaceful out here, save for the trafficking tankers. The Seto Inland Sea is an important shipping route, connecting three of Japan’s four main islands: Honshū, Kyūshū, and Shikoku. The tankers aren’t too disturbing, yet they’re present like a law of gravity, making it impossible to truly escape modern life.

The Benesse House Museum

The next day, we head to Naoshima’s main attractions, the Benesse House Museum and the Chichu Art Museum, both designed by architect Tadao Ando. Although not quite as imposing as Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim in Bilbao or Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim in New York, Tadao Ando’s Benesse buildings leave me in awe. Round corridors and interlinked spaces sit half-sunken in the Earth as to better fit into the environment. How does he get concrete to appear so warm and natural?

Inside the museum we find paintings of world-class artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jean-Michel Basquiat, but it’s not their best work. I’m far more moved by the artists who have been commissioned by the museum for site-specific works, such as Walter de Maria. His granite balls sit in their open bunker like artifacts from an alien civilization.

In the museum courtyard, I look at the photographs of Hiroshi Sugimoto for a long time. His work “Time Exposed” consists of thirteen black and white photos of thirteen geographically different yet equally calm seas. Twelve of the photos hang in two rows and form a link between the museum’s interior art and nature’s exterior draw—the real ocean, calm as in the pictures, is right there as a backdrop. It reminds me of how Japanese landscapers enhance their work by borrowing the beauty of distant sites. In the Shugakuin Imperial Villa gardens, for example, the Higashiyama mountains are part of the design. Sugimoto’s thirteenth photo hangs all by itself on a cliff and can only be seen from a dock. It’s my attention that joins everything together.

Does Naoshima Come True on its Promise?

After three days of visiting and revisiting the galleries, after walking up and down the pine-covered hills, after feeling my gratitude grow and my mind expand, it’s hard to remain a sceptic.

I cannot tell how environmentally healthy the island is. I cannot confirm that the locals are truly happy to see us—besides hosts and staff we didn’t meet anyone, except for one octogenarian who insisted on giving us her garden-grown orange. But the Benesse Art Site has undeniably brought life back to Naoshima by changing a wasteland into a responsible travel destination. Art has beautifully transformed the landscape and keeps transforming the people who come to explore its cultural sights.

By the end of the week, Daniel and I are dreaming out loud: Should we buy an abandoned house and convert it into an art space? Give up our nomad life and write here until the end of time? Open an artist residency?

We have many dreams such as these, yet rest assured: If we make any of them come true, you’ll be the first to know.

Time to Say Goodbye (and One Tip)

After Naoshima, we went to Teshima, Inujima, and Shōdoshima, the other art islands in the region. I’ll have to report on those some other time. Today I’ll leave you with one tip:

You can travel to the art islands at any time, yet real art buffs will want to go in 2025, when from spring to fall, the sixth Setouchi Triennale will take place. It’s recommended to make reservations ASAP.

All my best,

Claire

P.S. If anyone is interested in buying an abandoned house in Japan and turn it into a group project, please reach out!

Great post. Will be featuring in my newsletter this week!

I visited Naoshima more than a decade ago now. Do they still have the dilapidated James Bond museum/attic? It was the most charming part of my visit!

During my visit of summer 2017, I saw the photograph on the cliff from afar, and curious about it, I made a reckless climb the steep rocks up to see what it was. It wasn't until I got the to the museum later that I understood its meaning. A fun memory. Do they allow photography inside the museums now? When I went it was heavily restricted, and they handed out mini sketchpads and pencils for visitors to record their impressions.