Last week, while working on what was supposed to become this essay, my husband and I received the sad news that my father-in-law passed away. He was ill and eighty-four, so we had known his death was coming in a not too-distant future. Still, we were shaken and dislodged. With him we had lost the last parent between us.

So instead of writing to you today about how Japanese minimalism relates to mindfulness, I’ll let death steal my attention and explore what I can learn from how the Japanese deal with grief.

Forever Goodbye

On one of my first afternoons in Kyoto, I stepped into the coolness of a small tea shop to treat myself to Japanese matcha of a quality that’s never exported—a green dream come true. I greeted the saleswoman with a shy konnichiwa and later thanked her with a confident arigatou gozaimasu for letting me taste several senchas. So far so good: The few Japanese phrases I had memorized worked.

But when I said sayōnara upon leaving, a veil of discomfort passed over the woman’s face, and I asked whether I had mispronounced my goodbye.

“Oh, no,” she said, embarrassed and waving away my embarrassment. “It’s… we don’t say sayōnara here.”

“Too casual?” I asked.

She shook her head—a minimal movement.

“Too formal?”

“We say sayōnara when we part forever, when we will not see each other again.”

“Like when someone is ill and dying?”

She giggled. “When someone is… moving to a different city. The dead we see again.”

Gratitude for Having Known and Loved

I had briefly forgotten that followers of shintōism, Japan’s largest religion, believe that the spirits of the dead can visit the living. Spirits reside in a different world that’s neither like hell nor paradise. If descendants perform certain ceremonies, these spirits can briefly return to the world of the living. Especially during the autumnal and vernal equinox, known as ohigan, a time when the border separating the mortal from the spirit world is exceptionally thin.

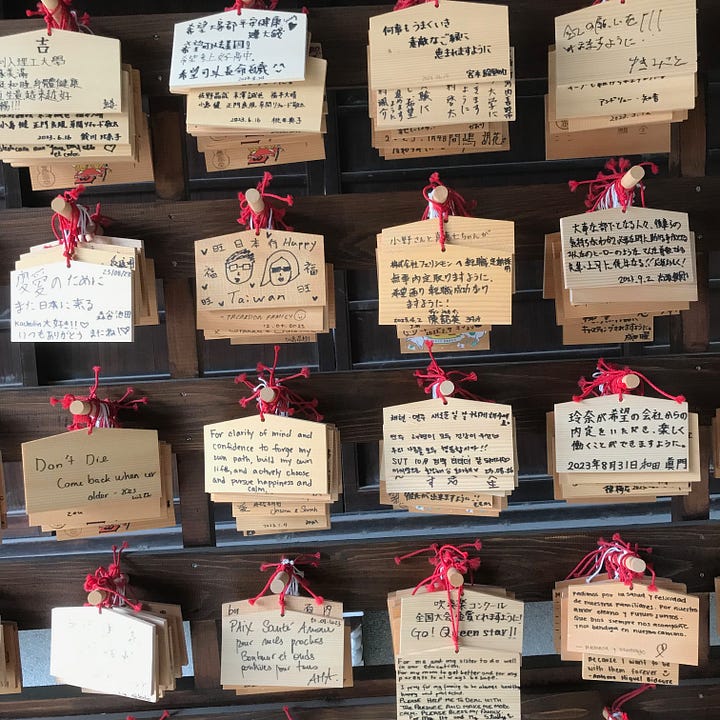

Spirits can also be called upon in ancestral shrines, which are everywhere in Japan—in homes, shops, and on the streets. I’ve seen locals offering snacks, flowers, words, gestures, and small bottles of sake to express their gratitude for having known and loved.

Real Life Ghost Stories

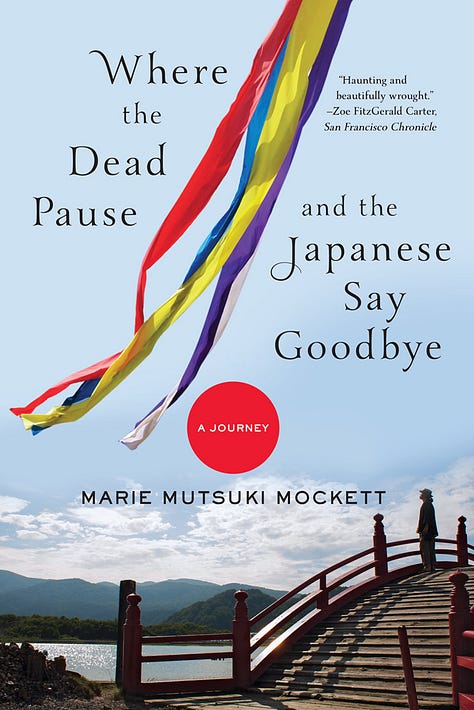

I learned about ohigan from Marie Mutsuki Mockett, who lost her American father in 2008 and long felt “hopeless about ever managing the voyage from grief to any semblance of ‘normalcy’ or ‘healing.’” After she traveled to Japan in 2013, where her mother was born, she wrote an excellent book about her literal and emotional journey: Where the Dead Pause and the Japanese Say Goodbye.

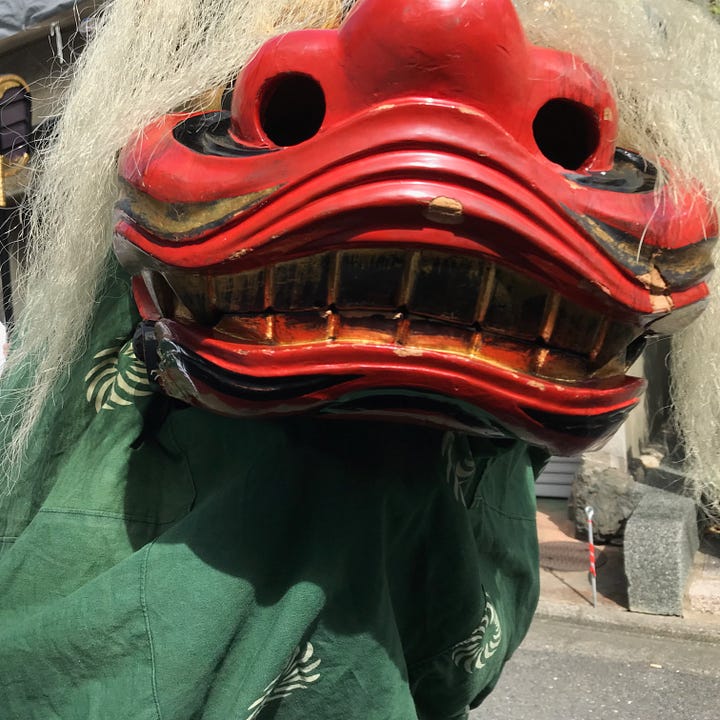

She arrived only two years after the devastating earthquake and subsequent tsunami that damaged the Fukushima nuclear power plant. Japan still mourned its thousands of dead and Mockett tagged along. In her search for consolation and meaning, she connected with family priests, Zen priests, and a multitude of bereaved. She traveled to Mount Doom, where the dead cross into the underworld, spoke to a blind medium, buried her grandparents’ bones, listened to real life ghost stories, and sent her lantern afloat on a river among hundreds of other lights.

One lesson learned was that her personal grief was but a small part in the communal grief of our species—she was not alone. A second, and in my opinion more radical lesson, was that the Japanese encouraged the living to continue their bond with the dead.

Consolation for Our Loss

How do we typically grieve in the West? From my experience, we recite prayers or poems, tell stories, write cards, sit shiva, bring flowers, and cook for the bereaved. Sharing memories is a wonderful ritual to help us navigate our loss. Memories give us the hope that the dead will live through us and survive.

But the messiness of mourning is accepted for only a limited amount of time. Ongoing grief is frowned upon. We’re encouraged to be tough and sever our bond with the dead. Get over it. Move on. Let go. And we wonder, Should we? It feels so unnatural to let go when all we want is go back.

Psychotherapist Gina Moffa says we live in a “grief-illiterate society” where people aren’t allowed to acknowledge their pain. In Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole, author Susan Cain writes, “We’re taught from a very young age to scorn our own tears (‘Crybaby!’), then to censure our sorrow for the rest of our lives.” Without an outlet for our grief, we risk shutting down emotionally, going dead inside, or numbing our pain with whatever we can find. Where is our collective experience as a consolation for our loss? Once the sense of community after a funeral fades, we can feel abandoned, if not cosmically alone.

Jealous of the Japanese

While my husband traveled to Florida to bury his father and spend time with his family there, I stayed behind in Kyoto to work (and spare us the cost of an expensive last-minute return ticket). I would be his emotional support when he returned—for as long as he desired.

Alone, I walked along the Kamo river bed, the water so low you could cross it with tortoise-shaped stepping stones, which I did. Or I meandered up the Eastern hills, near the Philosopher’s Path, sweating and slapping the mosquitos away from my wrists. Often, I sat on wooden stairs in shady Zen gardens and instead of just being there, present like a monk, I brooded.

Why was I so sure I’d never see my mother again? Why did I always deny what I felt when I sensed my father’s presence? How could I believe that their deaths were irreversible and keep longing for an impossible reunion?

I was jealous of the Japanese.

But even so…

The Buddhist poet Kobayashi Issa (1763–1828) is one of Japan’s great four haiku masters and penned over 20,000 haiku. He suffered a great deal of personal loss and wrote a haunting poem expressing his ambivalence toward death.

It is true

That this world of dew

Is a world of dew.

But even so…

Issa knew life was transient, yet wouldn’t accept this as a final answer. He lived with the contradiction—the truth of mortality and the even so.

Japan is known for its ambivalence, for its numerous homonyms that turn the simplest phrases into enigmas, for its near-infinite number of kami (divine spirits), for its vague definition of what a kami is (anything awe-inspiring), for preaching Buddhist detachment while building ancestral shrines, for its citizens saying “maybe” when they mean “no,” for its employees working dutifully for unappreciative superiors while seeking a kami’s blessing to be released from toxic environments.

Polarity as the Norm

In the West, we have difficulty reconciling two conflicting beliefs within ourselves. It may cause us cognitive dissonance. It’s true that the Greeks and Romans once worshipped multiple gods with clashing points of view, but we stopped taking lessons from the priests. We followed the philosophers instead. We learned their logic and reason and trained ourselves to see the distinction between idea and form, good and bad, wisdom and folly. And then Christianity indoctrinated us for centuries with the belief in only one god and one truth.

I’m drastically simplifying things, of course, but it’s no surprise to me why many feel uncomfortable holding two contradictory beliefs at once.

Post-structuralists such as Derrida tried to help us overcome our oppositional thinking, but I’m afraid Western thought has not advanced much in that regard, especially not in the United States where polarity seems to be the norm.

Bye Bye

Back to the Zen garden and me brooding there. Is it madness, I wondered, to know our loved ones are gone and still wait for a sign of life? To believe that our brains are writing our dreams and still feel consoled when our loved ones visit us during the night? Our life and our loss, our joy and our pain are already paired. Why not let our rational beliefs and our heart’s beliefs live side by side?

I made up my mind: I was not going to part with sayōnara anymore. No more forever goodbye. Bonds of affection are hard to break, so I would not break them. I would be like the Japanese school girls, who enliven the Kyoto streets in the late afternoon and repeat in innocent voices the cheerily English greeting bye bye when they part, convinced that they will see their friends again the next day.

I would read awe-inspiring haiku and let my tears drop between Issa’s dew. I would seek out my loved ones’ echoes in quiet places of beauty. And I would open myself to the possibility of a reunion—a dialogue, an image, a sense of connection. I might even clap my hands at a shinto shrine to let the kami know I had arrived. I would let my belief and disbelief comfortably coexist.

Maybe grieving can be like the leaves changing color in autumn, a dazzling array of shades to remind us that everything ends yet not all is lost.

Desk Journeys aka Book Recommendations

On grief

Quoted in this newsletter: Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole by Susan Cain.

Heartwood: The Art of Living with the End in Mind by Barbara Becker. The author speaks from both personal and professional experience when she writes, “Sometimes, as the great masters have taught, we have to die before we die if we want to truly live.”

The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion. The great author walks a path between her known life and insanity, imagining messages in order to survive, and keeping the hope alive that death is reversible.

Levels of Life by Julian Barnes. One of my favorite British novelists on life after losing his wife: “This is what those who haven’t crossed the tropic of grief often fail to understand: the fact that someone is dead may mean that they are not alive, but doesn’t mean that they do not exist.”

La Chambre Claire / Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography by Roland Barthes. The book’s subtitle could also have been: Reflections on mourning and coping with your own mortality. Barthes makes a lyrical case for how photography renders loss visible and how the spectator is in direct relationship with the subject through touching details. It’s an ode to photography and an eulogy for his mother, although some speculate it was an eulogy for himself: Barthes died unexpectedly soon after the publication of La Chambre Claire.

Last but certainly not least: All poems by Emily Dickinson, for whom the border between life and death was porous enough to cross at will.

On grief & Japan

Quoted in this newsletter: Where the Dead Pause and the Japanese Say Goodbye, by Marie Mutsuki Mockett.

I also highly recommend watching Journey to the Shore, a Japanese movie I was able to see on Kanopy (and if you’re a member of a public library in the US, you may have free credits to watch movies on Kanopy, too).

On Japan

Some of the best nonfiction on Japan I read is by the hand of lauded travel writer Pico Iyer. He arrived in Kyoto in 1987, settled there, married a Japanese woman, and has lived in Japan on and off ever since. For exquisite short insights into the Japanese culture, please read A Beginner’s Guide to Japan, which is, trust me, not your average travel guide. For a romantic view of Kyoto, descriptions of temple ceremonies, and an intriguing love story, I recommend his memoir: The Lady and the Monk: Four Seasons in Kyoto.

Time to Say Bye Bye

From here on out, you’ll probably hear from me more regularly in shorter posts. I’ve been afraid of scaring you away if I publish too much, but I imagine you’ve signed up to follow me on my journey, so I’ll stop being silly and share what I think is worthwhile in digestible chunks.

Feedback is welcome, in any form you see fit.

All my best,

Claire

P.S. Mary Oliver paved the way, as she so often did.

I have refused to live

locked in the orderly house of

reasons and proofs.

The world I live in and believe in

is wider than that. And anyway,

what’s wrong with Maybe?

From the poem “The World I Live In” in the collection Felicity by Mary Oliver, Penguin Press, 2015.

Beautiful post, Claire. There's a real bridging happening here, and it's heart-opening to read.

"I would read awe-inspiring haiku and let my tears drop between Issa’s dew. I would seek out my loved ones’ echoes in quiet places of beauty. And I would open myself to the possibility of a reunion—a dialogue, an image, a sense of connection. I might even clap my hands at a shinto shrine to let the kami know I had arrived. I would let my belief and disbelief comfortably coexist." So much love and healing in the mystery.

Excellent post, Claire, and you’ve made me realize that how we define the absence after death is something I want to come back to in my own writing. I agree that Marie’s book is well worth reading, and I appreciate hearing about the Iyer books. (I’ve read one of his—can’t think of the title right now—and loved it.) My condolences to you and your family —it’s so hard to be far away at times like this.