# 3 Living in a Traditional House in Kyoto

On light, manners, mindfulness, and the unfamiliar

I walked the grounds of a dozen temples, attended a full moon celebration, and joined a parade of geishas for the blessing of the comb. These are all extraordinary experiences, but what I enjoyed above all else in Japan was meeting the unfamiliar in the mundane.

As a novice in Japan, I experience the simplest things here as though for the first time. Catching a bus or shopping at a supermarket are activities full of wonder. I feel alert and marvel like a child. Look at this! What’s that? Oh, wow! I’m touched by the unexpected and get curious about everything I don’t understand. Whatever was normal—a relative concept—has become strange and intriguing.

The act of noticing is rewarding. I often find it difficult to take fifteen minutes to meditate, but paying attention to my surroundings as I move through the day, does not feel like an effort at all. That kind of mindfulness is pure joy.

Please join me today and live one ordinary day in extraordinary Kyoto.

Light

Morning light touches me through frosted glass. Only downstairs do we have one transparent window to include the mini garden into our two-story home. The other windows in our traditional Kyoto house are cloudy to guarantee privacy in the absence of curtains. The modest houses in our Kami-Gyoku ward are built close together yet do not share walls; we live intimately with our neighbors yet independently. During the day the frosted glass downstairs turns passersby on the street into ghosts. It almost seems intentional, considering how the Japanese bond with the dead.

Perspective

I sleep on the floor on a futon that’s thinner than an average mattress yet surprisingly comfortable. It makes me feel I’m camping, yet in a good way: with the trill of adventure and without the discomfort of a leaking tent. Beside me on his own futon sleeps my husband Daniel, probably dreaming of Totoro.

The floor is covered with tatami mats that smell like dried grass. It enhances the impression of camping, of living inside nature.

Room sizes in Japan are measured by tatami mats. Our bedroom has six and is separated from the bathroom and the front room by sliding doors. Next to the front room is a guest room with a bed we’ve chosen not to use. It’s so much more fun to go camping each night.

Movement

Getting up from the floor is exercise. I squat and push myself to standing in a rise that is so sudden, it’s dizzying.

I slide open the wooden doors and split the painted landscape, cherry blossoms to the right, pagoda to the left.

On the parquet floor below, I stretch my morning into yoga and count myself lucky. Butterflies visit the mini garden in a lively flutter while the neighborhood mouse scurries by to drink from our mini pond. Palm fronts rustle against the wooden fence. The neighbor’s wind charm chimes.

Magic

Things happen in the house without my doing. When I sit on the toilet, the fan flips on. When I stand up, the toilet flushes itself. When I turn on the stove, the exhaust starts sucking air out of the room. When the washing machine is finished, it plays a victory song. When I change a setting on the air conditioning, the thing speaks to me like a domestic spirit.

Perspective and Movement

The dinner table is my work table for fifty percent of the time. Daniel and I tend to share things equally in our household. I sit at the low wooden table on a thin square silk-encased pillow on the floor with my legs down in the wood-covered pit below. The room, and thus the world, looks different from this angle. I am smaller, relatively less significant—a soothing perspective.

When I work upstairs at the coffee table, I sit on the tatami mat floor with my legs crossed in front of me, a position I can hold a little longer each day.

Getting up from either table requires the same squat and push as getting off the futon. This is how Japan will transform my body.

Manners

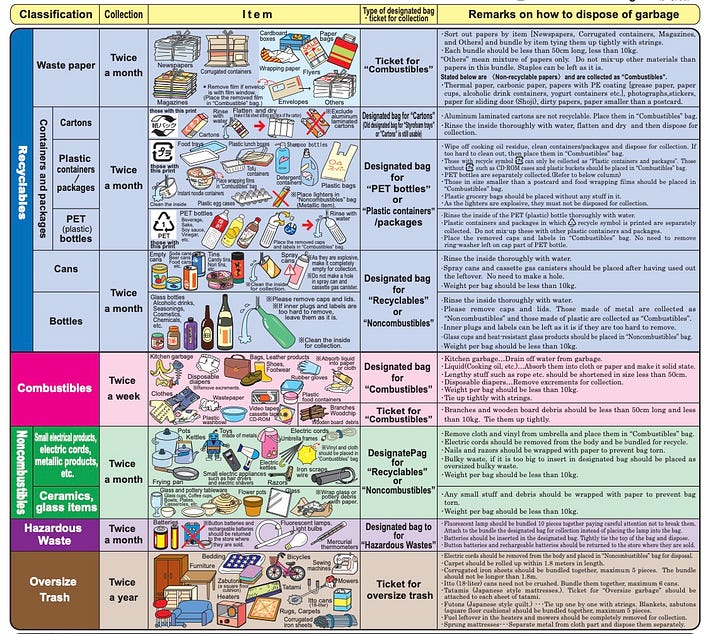

After a breakfast that includes the most delicious green tea I’ve ever had, I separate our trash into five excessively detailed and therefore utterly confusing categories. Twice a week, I put my burnables on the stoop in a yellow bag that I cover with a blue netting to protect my trash from the crows.

Today, as I leave my tightly-bound bundle of recyclable cardboard on the stoop, one of the workman doing renovations next door stands outside eating his lunch. Upon seeing me, he straightens his posture and bows as though I’m royalty. I bow back, probably deeper than I’m supposed to. The courtesy of the Japanese workmen is disorientating. They come to the door to apologize in advance for the noise they might cause. They don’t shout orders and seem to whisper to one another only when necessary. They don’t smoke in front of the house, don’t play the radio, don’t bang doors. They work in full awareness that their labor, although necessary and paid for, is a gross inconvenience.

Strangeness Galore

I bicycle through the city on the left side of the street or on the sidewalks, which is legal and recommended. The frequent city buses tend to cut off cyclists when the chauffeurs need to make a stop at the curb. People waiting for the buses line up on the sidewalks in neat single-person rows, never blocking the path for cyclists.

Young apprentice monks in grey robes hold shopping bags and stand awkwardly rubbing shoulders with one other like normal teenagers as they wait to clatter across the road on their geta (wooden sandals). The green light for pedestrians tweets like a bird. Even with all roads completely empty, nobody disobeys the signs.

Kids no older than six walk home from their primary school in small giggling clusters unaccompanied by an adult. Their backpacks are so huge compared to their tiny bodies, that I fear they may topple over on an incline. Japanese tourists dressed in rented kimonos pose underneath a roadside Torii gate.

I park my bicycle in an unmanned garage by pushing my front wheel into a slot until a lock engages. Leaving your bicycle on the street is illegal. Later, when I’m ready to leave, I will swipe my transportation card (that I can also use to pay in stores) to free my bicycle.

I browse a secondhand market where the clothes are of such high quality and low prices, that I vow to arrive with an empty backpack next time I travel to Japan.

Taste

On my way home, most shops are already closing, shutters rattling down—it’s not even six.

The excellent sushi prepared in our supermarket gets discounted after dusk and I pick up a tray with nigiri. Surprise fish, I call it, since half of the time we don’t know what we’re eating until we sample the pieces in our mouth, judge their flavor and texture. Sometimes the fish remains a mystery even then. Could this be sea cucumber?

We pour cold sake from what resembles a half-liter milk carton and munch on pickled vegetables I cannot name. When we prepare soba noodles or grill fish, we add pastes, herbs, and spice blends that make us wonder how we ever survived without them. Shiso, miso, furikake, neri goma, shichimi togarashi. The words themselves are delights. And then the mushrooms!

Dreams

Full with the foreignness of one single day, I fall asleep on my futon and dream of cranes.

Desk Journeys aka Book Recommendations

A great way to get a feel for a country, other than living there yourself, is to read its literature. I limit myself to recommending one book in translation by ten Japanese authors I admire divided in two categories. I’ll let the books speak for themselves.

Contemporary female authors

Banana Yoshimoto, The Lake—“It was so gorgeous it almost felt like sadness.”

Sayaka Murata, Convenience Store Woman—“You eliminate the parts of your life that others find strange—maybe that’s what everyone means when they say they want to ‘cure’ me.”

Yōko Ogawa, The Housekeeper and the Professor—“A problem isn’t finished just because you’ve found the right answer.”

Natsuko Imamura, The Woman in the Purple Skirt—“I’ve been here all along.”

Classic male authors

Kōbō Abe, The Woman in the Dunes —“You can’t really judge a mosaic if you don’t look at it from a distance. If you really get close to it you get lost in detail. You get away from one detail only to get caught in another. Perhaps what he had been seeing up until now was not the sand but grains of sand.”

Yasunari Kawabata, Palm-of-the-Hand Stories—“A child walked by, rolling a metal hoop that made a sound of autumn.”

Natsume Sōseki, Kokoro—“I bear with my loneliness now, in order to avoid greater loneliness in the years ahead. You see, loneliness is the price we have to pay for being born in this modern age, so full of freedom, independence, and our own egotistical selves.”

Kenzaburō Ōe, A Personal Matter—“More often than not he finds what he is looking for, and it destroys him.”

Haruki Murakami, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle—“What we see before us is just one tiny part of the world. We get in the habit of thinking, this is the world, but that’s not true at all. The real world is a much darker and deeper place than this, and much of it is occupied by jellyfish and things.”

Kakuzō Okakura, The Book of Tea—“Nothing is more hallowing than the union of kindred spirits in art.”

Time to Say Goodbye

That’s it for now. I’ll be in Japan for another six weeks, so I’ll have more opportunities to share my experiences of this inspiring country.

All my best,

Claire

P.S. You can find more posts on Japan in my archive.

I felt transported to Kyoto as I read this beautiful post. ❤️