# 5 Possessions as a Liability: Illegal Dumping is a Disgrace

On the Japanese Alps, minimalism, and getting rid of things in Osaka

We survived our two weeks in the Japanese Alps and did not encounter any black bears. This is no doubt because everyone around us was nervously ringing their black bear bells. We did, however, meet a handful of unthreatening snow monkeys.

The Japanese Alps in autumn foliage are stunning. They are also accessible by public transport (cable cars galore!), crowded with domestic tourists, and walkable by non-experienced hikers like us. Each location has its own local food speciality (not always worth the price) and by the end of each day, you can enjoy an onsen (hot spring), where maple leafs float among your tired limbs.

Our time in Japan is coming to an end. Before we leave, I have one last piece for you on Japan, and on how their laws on waste and recycling makes me embrace minimalism all the more.

Happy reading!

Possessions as a Liability: Illegal Dumping is a Disgrace

I learned the value of minimalism when Daniel and I lost our home in Paris in 2019 and crammed a lifetime of things in a corner of boxes. I recognize this value monthly when I pay our storage space bill. And each time I carry my luggage, I feel the weight of my possessions.

Not having a home saves me from overbuying. I coveted the extraordinary carpets in Oaxaca, the hand-crafted shoes in Hoi An, and the ancient chipped tea cups in Kyoto, but I was never truly tempted to purchase anything. At least not for myself. What can’t travel with me on my back doesn’t interest me. Where’s the joy in storing something in a box?

When I first arrived in Japan in September, I had expected minimalism. But I landed in Osaka, a city of excess: bright screens, sizzling food stalls, razor lights, streams of people, giant commercial signs, hostesses in cosplay costumes, and mighty mechanical crabs on restaurant facades.

It was also in Osaka, however, on my way out of the country, that I felt forced to rethink my consumption patterns and vow to buy less.

I don’t typically self-medicate through shopping. I’m mostly unaffected by society’s pressure to consume without bounds. But let me roam free in a second-hand store that sells high-quality Japanese-made clothes for €3,50 per piece and I will find something I absolutely must have to redefine myself. Daniel, too, couldn’t resist the temptation, and picked up items he didn’t actually need for our two-week trip across the Japanese Alps.

When I unpacked the bag we had shipped from Kyoto to our hotel in Osaka and heaped everything onto the bed, I felt gloomy at the sight of so many beautiful clothes. Far more than we could bring to Bali. We had to get rid of cashmere sweaters and linen jackets and do so in a responsible way.

In Kyoto, I’d been introduced to a complicated garbage system. I put combustibles in yellow bags and plastics in white bags and put both on the street on different days. I delivered my PET bottles, milk cartons, and cans in collection boxes at the grocery store, and tied plastic ribbons around neatly flattened and stacked cardboard. I never learned, however, what to do with good reusable clothes other than return them to the Second Street store where I’d bought them.

On the day we left Japan, with just hours to kill, we made a trip to such a store in Osaka.

“Do you have a Japanese passport?” the sales clerk asked me.

I shook my head.

“A residence permit?”

Nope.

“I’m sorry: We cannot buy your clothes.”

Was this an unwilling clerk, a store policy, or a regional law? In Kyoto my Dutch passport had been enough.

We tried another location, then another chain, each time with the same result. Sorry.

I offered to donate the clothes to the stores, yet nobody showed interest, as though accepting donations was illegal. Once, I suggested I give our items to the shop girl personally. So she could then gift or sell it herself. Without offering a reason, the answer remained no.

Next, I googled recycling centers. There were three between our current location and the hotel from where we’d leave for the airport in an hour. We zigzagged to all three, yet none of them were open or could be found.

What to do?

Japan does not have public trash bins on the street; you must carry your garbage with you until you can dispose of it somewhere properly.

Walking past a laundromat, I suggested to leave the clothes on the packing table, free for all. But Daniel noticed a security camera and mentioned something about facial recognition and not wanting to be banned from ever entering Japan again.

He thought we might “accidentally” forget a bag with clothes at the train station while wearing face masks, a plan I vetoed. An abandoned bag at a train station is suspicious and might be seen as a terrorist risk that must be destroyed with explosives.

Could we leave it in a coin locker? It would only cost us a few dollars, and after the 24-hours ended, the door would open and whoever found the bag would make use out of its content. Or resent us.

We walked past a dumpster in an alley with no one to spy on us. Could we drop our bag there? Daniel scanned the sign above with the Papago app to translate the message, making sure it was indeed a dumpster. The sign read: Illegal dumping is a disgrace.

(A question I won’t get into yet ponder: How does this relate to their dumping of contaminated Fukushima waste water into the ocean since August 2023?)

Back at the hotel, we asked the two young women working the desk what we could do with our leftover clothes. They looked at us as though we’d asked them to solve a complicated equation.

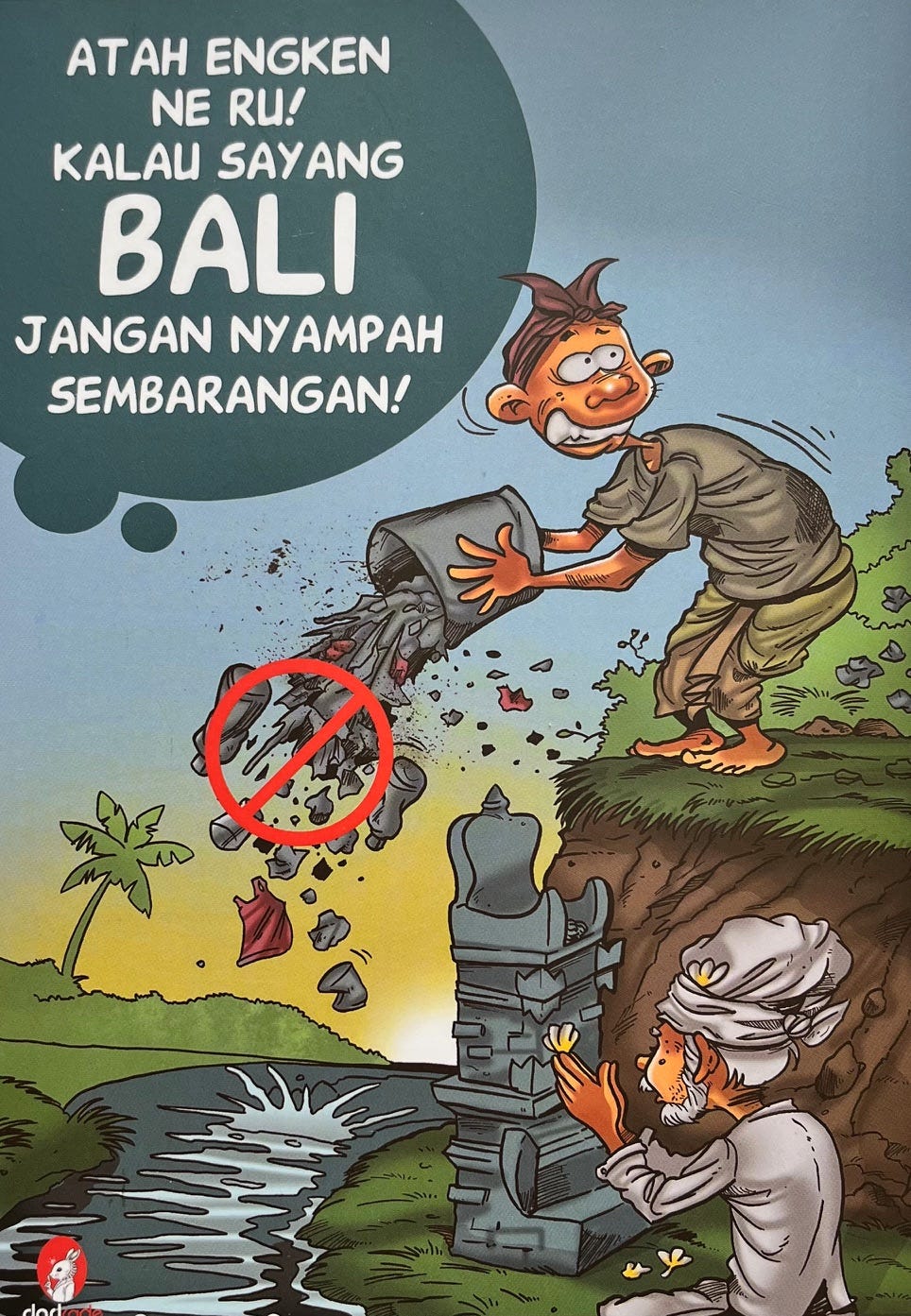

We reconsidered an earlier idea: bringing everything to Bali. We counted on less laws there and more interest in donations. Then again: half of our clothes were useless in the tropics and the airline imposed strict luggage restrictions.

Finally I told the door man: “We have some garbage we cannot take on the plane. Where can we leave it?”

“Give it to me,” he said.

I handed him the backpack with clothes.

“All of this?” he asked.

I nodded. I wanted to say: Please use what you can, give it way, bring it to a refugee center—it’s good stuff. But I kept my mouth shut, afraid that such suggestions would make this exchange illegal.

On the way to the airport, I thought of how even a short period of overconsumption had caused a problem. I had purchased things just because they were cheap and second-hand and I desired them. And I vowed to be more mindful with my purchases next time.

Is this an indication that Japan’s strategy works? I believe so. By making the consumer more responsible for discarding their unwanted stuff, they become more aware of the problem and might contribute more to the solution by consuming less.

My parents and grandparents belonged to generations who believed that gathering wealth and possessions equaled freedom. The more they owned the less they worried about the future, about life after retirement.

I want to belong to a community who believes trading books, time-sharing houses, and borrowing gear is the way to break the chains. The liberated are the people whose belongings burden the world (including themselves) the least.

Author Update

After receiving feedback from my agent, I’m back at editing the memoir for which I have yet to find a striking title. It’s about elder abuse, family dysfunction, losing three parents during a global pandemic, and other stressful circumstances that made us travel from Vietnam to Florida and from there to the Netherlands and back to the US. I’m hopeful this book will find a good home next year and I’ll be able to share the full story with all of you.

Time to Say Goodbye

Stay tuned for upcoming dispatches on Bali. Is it the paradise many claim it is or the polluted and overbuilt disappointment critics report it to be? And how does it feel for a Dutch person like me to visit an island that suffered under the Dutch colonial rule?

All my best,

Claire

P.S. Any particular questions about Bali? Feel free to ask them in the Substack comments or drop me a note.