# 42 Less than Jubilant Takeaways from 6 Years of Nomad Life

On the shadow sides of the world and what we can do in response.

I’m Claire Polders, nomad and author of six books. Wander, Wonder, Write is my publication on mindful traveling and the writing life.

This post is the counterpart of Uplifting Takeaways from 6 Years of Nomad Life.

Prologue

My husband, Daniel, and I have been nomads since 2019, when we lost our home in Paris.

We ran into challenges during the pandemic, and had a few unpleasant experiences with fake guides and non-metaphorical leeches, but overall we’ve thoroughly enjoyed our traveling existence. It has transformed me into a more positive person.

Today, however, I’d like to share what nomad life has taught me about the shadow sides of our world. Not to encourage despair yet rather as an opportunity to reflect. How may we improve upon what we find?

This is how I strive for balance, placing bad news on a bed of hope.

I could write an essay on each of the following 5 subjects—and probably will—but because I’m making a list now, I’ll keep it brief. Whatever I leave unexplored may find its way in future posts.

1. Nature is in serious distress

We’ve witnessed excessive rainfall causing deadly floods in South Korea and were there for the devastating forest fires in Los Angeles. During our adventurous ride up a mountain in Central Vietnam, we passed countless logging trucks, bringing down newly killed trees from the forests around Mang Den. We had trouble breathing in Bangkok and more recently here in San Miguel de Allende (Mexico) where air pollution is exacerbated by draught. Coffee farmers in Colombia worry about their future because of unpredictable seasons, and locals everywhere have told us that the weather is not normal, not like it used to be.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that nature is in serious distress. But it was one thing to read and hear about it, quite another to encounter the dire symptoms of our unsustainable world everywhere we went.

Seeing the bleached coral reefs off the coasts of the Galápagos was probably the most devastating experience for me. Aquatic life is so rich around these islands because of five major ocean currents that used to reliably raise and lower water temperatures. But climate change has brought more frequent and more extreme El Niños to the region with a destructive effect. When coral is stressed by heat, it expels the color-giving algae that they feed on. Bleached coral is starving coral. Reefs can survive for a while and gain back their health once circumstances improve, but not for consecutive seasons. Swimming above a bleached coral reef is like swimming above a graveyard scattered with fractured bones.

How can we do better?

I don’t write about climate change much, because it makes me feel like a hypocrite. How did I get to the Galápagos if not on a plane? Why won’t I commit to being a full-time vegan?

The natural world obviously needs our protection. Some admirable people become activists, donors, volunteers, or Green Party politicians. Most of us try to help by voting for the right people and limiting the things we know will harm our planet. We can all become more mindful consumers by curbing our energy consumption. We can buy less clothes and gadgets, shop secondhand and create less waste. We can favor public transport over renting a car or making short-distance flights. We can eat more local and seasonal foods. We can limit (or eliminate) our meat consumption. We can seek out eco-conscious accommodations and sustainable travel experiences. We can do all or some of these things while not making life too miserable for ourselves. Most important is that we answer to our own conscience, trying to align our beliefs with our behaviors, and do the best we can with the tools we have and the cards we’ve been dealt.

2. Plastic Waste is Everywhere

Bali is infamous for its plastic-clogged rivers, but plastic waste is overflowing from dumpsters in Sicily, litters the beaches in Greece and Vietnam, and soils the streets in Thailand. Plastic covers the vegetables on the farmer’s market in Itoshima (Japan) and in supermarkets across the Netherlands. In San Miguel de Allende (Mexico) street food is often served on reusable plastic plates wrapped in thin plastic bags: After a meal they replace the dirtied plastic cover instead of washing the plate.

Even in the so-called protected nature reserve known as the Galápagos Islands, plastic water bottles were for sale everywhere and consequently ended up in the bays where the sea lions frolicked.

How can we do better?

We don’t always have a choice as a consumer, but we can pay more attention and recognize those moments when we do. We can bring our own shopping bags to markets and stores. We can refuse straws and plastic cups and cutlery. We can wash ziplock bags and reuse them. We can discard of plastics properly, separate burnables from recyclables. We can ALWAYS leave the house with a reusable water bottle and simply ASK whenever possible whether a waiter or barista is willing to fill it up (perhaps for a small fee). I’ve been pleasantly surprised by how much a polite request for drinking water can accomplish, even at an airport coffee shop where the goal is to sell you that $4 plastic bottle of water (and the faucet water isn’t drinkable).

Yes, I know that restaurants survive on selling beverages, and I have no problem ordering water and paying for it, when they do so in a sustainable way. But when they serve plastic bottles… I just can’t.

3. The World is Awash with Misinformation

I believe in the transformative power of knowledge. If I want to know where a country stands politically and socially, I look at its educational system. How well can average citizens emancipate themselves through knowledge? How independent are schools and universities?

The internet has been instrumental in democratizing the access to information, empowering people worldwide, but it’s also become a source of misleading noise and untruth. Engagement-driven algorithms amplify popular content and bury voices who dare to differ.

Some people call this the information collapse: We can no longer rely on what we read. Particularly on the lying internet.

Daniel and I often set off toward a place with a preconceived idea of what to expect, yet soon after arrival, reality corrects us. Must-see waterfalls turn out to be dribbles, and an easy hike to a temple proves to be a 3-hour trek on unpaved roads without shade. The blogs and reviews we’ve read were probably AI written or copied from pages filled with tourist propaganda. Even Google maps is often wrong. The lesson: Always ask locals for advice.

How can we do better?

For personal traveling, the information collapse is a nuisance and a potential trap. For the future of our social and political world, it is a disaster. So becoming as alert as possible to any misinformation is essential. When I read something not coming directly from a trusted source, my first response is distrust.

Who is telling me this? What are their interests? What’s this knowledge based upon? Have others verified or falsified these statements?

Equally important is to not contribute to the problem. Telling the truth matters more than ever. I try hard to never share information based on hearsay. I write about things based on my own experiences without extrapolating too much. Having one bad experience in a village doesn’t mean the entire community there is unreliable. I have a positivity bias, meaning: I tend to write about what I like and keep silent about what disappoints me. Knowing this about myself, I always scan my articles to make sure I’m not giving a false impression of a place. Lying by omission can be misinformation, too.

For more about this subject, please read: How to Judge Travel Recommendations: Trap or Treasure? On finding what matters to us in a world of misinformation (and a bit about Bali).

4. Suffering is the Other Side of Paradise, often Literally

As aware as we all may be in our first-world lives of widespread inequality, I must admit that I had been shielded from the effects of true poverty and suppression until I began traveling farther afield.

In rural North Vietnam, I met school-aged children carrying harvested loads on their backs, serving meals to tourists in family restaurants, or begging for money on the streets. In Thailand our hotel felt the need to put up a sign banning child prostitution, which only told me how common the crime there must be. In Mexico and Colombia, we saw fathers bringing their children to dumpsters so they could help sort through trash—refugees from Venezuela, we were told. At a tea plantation in Sri Lanka, women my age and older work twelve hours per day, barefoot in the full sun.

And then there were the stories we inevitably heard from reliable sources about child brides being trafficked to China, forced factory labor, landmine-maimed locals, and people surviving on one bowl of rice a day.

In short: There is more suffering than I know how to address.

How can we do better?

I have no real answer, obviously. During our travels, we can seek out local businesses and purchase their products and services. We can give money to individuals or local organizations who work on improving the conditions from the ground up. We can become volunteers. But will it ever be enough?

The problems caused by inequality are so huge and systematic, that it often makes me feel powerless. But I have a moral ambition and am educating myself on how to respond more effectively to the problems I encounter. (More about that in newsletters to come!) For the moment, I remind myself that I always have the opportunity to show respect and be kind. Respect and kindness may not change another person’s life, but they are not without value.

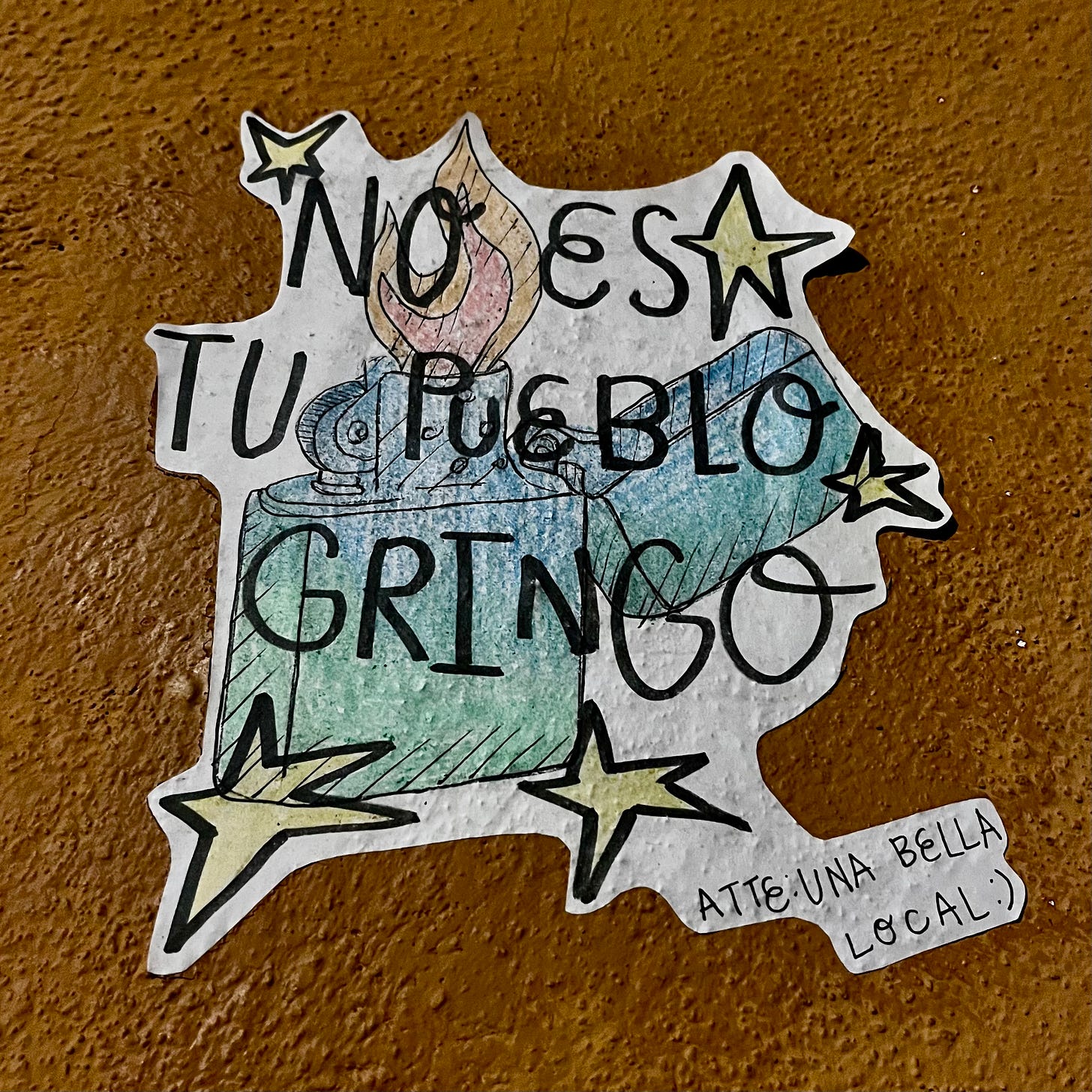

5. Overtourism Destroys Destinations and Experiences

Tourist numbers have exploded worldwide since the pandemic. People want to get out there and explore before it’s too late. But when we flock to places in great numbers, we often ruin the beauty or authenticity we came to see.

The summer crowds in Amsterdam have turned a neighborhood market into a farce. Visiting Rome among the crowds was a challenge and made us seek out hidden gems. The serenity of certain Kyoto temples has been sacrificed to congestion, and recently in Colombia, the transformation of a once dangerous district left me dubious of its popularity.

Other destinations, such as Ubud and Seminyak in Bali, are ruined by over-construction. Cement, noise, and exploitation are dominant. Construction workers often sleep inside their unfinished buildings or in makeshift camps on the side. In San Miguel de Allende, we lived next to a house that was being built from bricks with no apparent heed to future earthquakes.

How can we do better?

Government regulations seem to be the quickest way to fight overtourism and over-construction. Only authorities can enact measures such as limiting tourist numbers, banning cruise ships, raising fees, and restricting AirBnBs. But tourism is big business, sometimes the largest source of income for a place, and economic interests often win from human interests.

As travelers, we can stop making bucket lists based on other people’s bucket lists. We can find destination dupes or journey to lesser visited regions. We can travel in the low or shoulder season.

Daniel and I once made the mistake of visiting a dive bar that the NYT had mentioned in their 36-hours in Bangkok article. The neighborhood was nearly deserted at 11pm, but that one bar was full of Silicon Valley tech bros spending as much money on their cocktails as they did back home. We left laughing at our own stupidity and soon found a local haunt where we drank some Singha beer.

I admit: it’s not always possible or desirable to avoid tourist hotspots. Sometimes we happen to be near a highlight at what seems to be the wrong time. Daniel and I will visit Machu Picchu and the sacred valley this August. Going to one of the world’s most popular destinations in peak season seems like asking for trouble. But it might be alright. Peru, having suffered from overwhelm for years, has developed a way to limit visitors and spread them across time and space. Theoretically, it should never get too crowded. How it will practically turn out for us is something you can read in upcoming episodes of this newsletter.

Epilogue

Have I listed all that is wrong with the world? By far not. I’ve selected only the issues I encountered most frequently during our travels or that touched me the most.

What about the things that are right with the world? If you need a more positive view, please read this post’s counterpart Uplifting Takeaways from 6 Years of Nomad Life.

Author News

My new book Woman of the Hour: Fifty Tales of Longing and Rebellion will be released in less than a month and is available for preorder now.

For The Brevity Blog, I wrote about how poetry helped me write this collection.

Related Essays

If you enjoyed this post, you might also be interested in reading:

Time to Say Goodbye

As this newsletter is published, Daniel and I are on our way to the Yucatán peninsula. The best flight to Lima left from Cancún, so we decided to take in a week of summer before heading to Peru’s winter. Next week, I’ll be writing from a little Mexican island.

All my best,

Claire

P.S. Your ideas on how we can all do better are very welcome.

Thank you—very powerful. Travel opens eyes and makes me more aware of my own imprint on our struggling planet. I am trying to be more conscious of the choices I make.

Thank you for compiling this list, for admitting the part we travelers play in all of it, and for thoughtfully considering what we can do better. In my own nomadic life (officially one year in as of July 4 🎉), I have witnessed/experienced all of these, but you have summarized them especially well. I look forward to deeper dives on any of these subjects, as well as tales from the island. 💜